installing statistical tools on a remote Linux machine

26 Dec 2013If you have lots of data to analyze you may need to use a remote machine to get the computing power you need. Amazon Web Services is a popular choice, but their machines usually come “naked” - they have the operating system and not much else. Amazon does offer some software bundles, called Amazon Machine Images (AMIs), but these are more about business tools (SQL and NoSQL applications mainly) than about scientific computing tools. So normally you need to install all the software yourself. That can be a pain; you have to rely on the command line (no clicking on .dmg or .exe files), packages have complex dependency relations, you need to figure out what compilers you need, etc. So here is a step-by-step. I’m assuming a few things: you know (or can figure out on your own) how to fire up a remote machine (say, an Amazon EC2 instance); you know how to SSH into your remote machine; you know what a terminal is; you are not afraid of Linux; you will use Python for your scientific computing.

So you have fired up your remote machine and it is running some sort of Linux - say, Ubuntu. The first step then is to update and upgrade the pre-installed packages, which are almost surely old. SSH into the instance and run the following on the terminal:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get upgradeIf you skip this step you may get in trouble later on: you will try to install your packages but you will get error messages saying that the packages couldn’t be found. That’s because of outdated repository information. So, make sure you always update and upgrade everything first.

If you have never seen these commands before, don’t worry. “apt-get” is a package manager that comes pre-installed on Ubuntu. You use it to install, update, and uninstall packages. Now, Ubuntu don’t just let anyone do whatever they want on the machine. If you try simply “apt-get update”, without the “sudo”, you get an error message saying that you don’t have permission to do that. Installing software is a potentially risky task, as it can break the system, create security holes, etc, so only a “super user” can do it. That’s why you need to put “sudo” before “apt-get”: “sudo” stands for “super user do”; it’s a way to tell Ubuntu to treat you as a “super user” and let you do whatever you want. On a local machine you would be prompted for your password, but on Amazon instances there is no such thing. So, that’s all that’s going on here, nothing of particular importance. If you are using a different Linux distribution - say, Fedora, Red Hat, or CentOS - the equivalent of “apt-get” is probably “yum”.

Next you need to install some low-level stuff that will be required by other, higher-level packages later on.

sudo apt-get install build-essential libc6 gcc gfortranYou now have the basic tools to compile packages from source. “Compile from source…?” Not to worry if you’ve never heard of this before. Many packages are easy to install: you just do “sudo apt-get install XXXXX” and that’s it, package XXXXX is installed; the binary files - i.e., the executable files - are generated automatically. Other packages, however, can’t be installed via “apt-get” and require instead that you get the source code and generate the binaries yourself. That’s what compiling is: transforming source code into executable files. To do that we need to install a compiler first. That’s what you just did above: you installed gcc, which can compile C code, and gfortran, which can compile Fortran code (and a few other helpful tools as well).

Now on to some statistical tools: BLAS and LAPACK. These are linear algebra packages. They have routines for solving linear equations, matrix factorization, least squares, etc. You won’t interact with BLAS and LAPACK directly though. They are low-level tools. They are intended to be used by other programs - like Python or C or R –, not by humans. (Well, you can write BLAS and LAPACK routines directly but you probably don’t want to.) You want to install BLAS and LAPACK because the programs you do interact with, like Python or R, can run faster if BLAS and LAPACK are present.

You also want to install ATLAS. ATLAS is a “bundle” of BLAS and (parts of) LAPACK but optimized for your specific machine. In other words, it’s BLAS and LAPACK but faster. Thus, in theory, we either install BLAS and LAPACK or we install ATLAS. In practice, however, some packages look specifically for BLAS/LAPACK while others look specifically for ATLAS, so it’s best to install all three.

BLAS and LAPACK first:

sudo apt-get install libblas3gf liblapack3gfThen ATLAS. This one is actually scattered across different packages:

sudo apt-get install libatlas-base-dev

sudo apt-get install libatlas-dev

sudo apt-get install libatlas-doc

sudo apt-get install libatlas-test

sudo apt-get install libatlas3gf-baseThat’s it.

If you really want to make the most out of your machine you may consider installing Intel’s Math Kernel Library (MKL) as well. It’s built on top of BLAS and LAPACK, like ATLAS, but adds many routines of its own. The benchmarks look really good, especially on multi-core machines; MKL gets increasingly faster than ATLAS the more cores you have (though there are lies, damn lies, and software performance benchmarks…).

Unlike everything else in this tutorial MKL is not open source. It costs $499 by itself, but to get it to work you also need Intel’s C++ compiler, so you will need a bundle like Intel Composer, which includes everything and costs $1,199. Licenses for non-commercial use are free though. If that applies to you then what you need to do is download the installer, run “sudo bash install.sh”, and follow the instructions.

Installing Intel Composer is straightforward, but by itself it won’t do you any good. You need to link your high-level tools - R, NumPy, etc - to MKL. I.e., you need to tell your statistical packages that they are supposed to use MKL. And there is no generic formula for that, it differs for every package and system. The only constant is that the process always involves banging your head against the wall. You need to figure out how to set the environment variables correctly so that the system can find your Intel compilers. You need to figure out what flags to use during the build phase. You need to read through dozens of pages of installation logs to figure out what went wrong. It may take days and it is not for the faint of heart.

Moving on.

Here are a few tools needed to build some Python packages:

sudo apt-get install python-dev python-nose cythonIn case you are curious, python-dev contains header files and static libraries needed for code distribution; python-nose is package for testing Python code; and cython allows you to mix some C code in your Python scripts.

Now on to HDF5. HDF5 is a suite of packages that let you store data in h5 format. The h5 format is optimized for loading speed: it takes more disk space than other formats (say, csv), but on the other hand it loads from disk to memory much faster. I think the trade-off is worth it; disk space is cheap (under $0.10/GB/month on Amazon), but powerful computers aren’t (up to $4.8/hour on Amazon), so it’s better to minimize computing time than to minimize disk usage.

Moreover, as Francesc Alted alerts us, the bottleneck in scientific computing is no longer CPU power but input/output (IO) speed. Our CPUs have become much faster but our disks only a bit faster; hence there is often a huge gap between what the CPU can do and what the disk allows it to do (the “starving CPU” problem). In my own research switching to h5 files reduced loading time in half. That is imaterial if your model runs in milliseconds, but in the world of big data your model may take hours or days to run, so halving the time makes a lot of difference.

To get HDF5 all you need to do is download the files and move them to the appropriate folders. No need to “sudo apt-get…” anything or compile anything from source. Just do this:

wget http://www.hdfgroup.org/ftp/HDF5/current/bin/linux-x86_64/hdf5-1.8.12-linux-x86_64-shared.tar.gz

tar xvfz hdf5-1.8.12-linux-x86_64-shared.tar.gz

cd hdf5-1.8.12-linux-x86_64-shared

cd bin

sudo cp * /usr/bin

cd ..

cd lib

sudo cp * /usr/lib

cd ..

cd include

sudo cp * /usr/include

cd ..

cd share

sudo cp -a * /usr/share

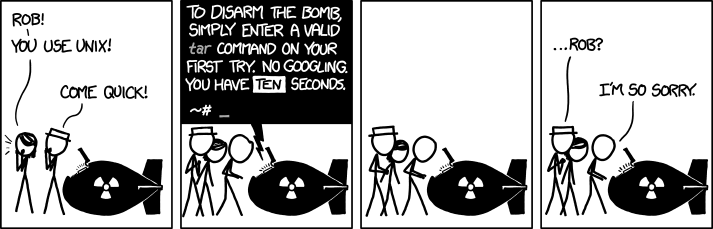

cd ..In case you’ve never seen it before, the “tar” command is similar to the “unzip” command on Windows. The .tar.gz extension indicates that the file is in a “tar ball” format and the “tar” command “untars” it. (Now, about that “xvfz” option…)

</img>

</img>

That’s it. There is really no actual installation involved with HDF5 here, you just download stuff and move it around. You won’t use HDF5 directly. You will install PyTables, which is the Python module that communicates with HDF5 and enables Python to handle h5 files. But PyTables is still a bit low-level, so on top of that you will install pandas, which uses PyTables to let you read and write h5 files in an easy way. More on these modules later.

(Take a moment to appreciate how lucky you are. If you were on a Mac you would need to compile the source code manually, as there are no HDF5 binaries for Mac, and you would need to read through eight single-spaced pages of instructions about which compilers to use, which flags are appropriate in each case, etc.)

Let’s move on to installing Python’s own packages. The first one needs to be setuptools, as some packages will rely on it.

wget https://bitbucket.org/pypa/setuptools/raw/bootstrap/ez_setup.py

sudo python ez_setup.pyNow on to NumPy, which gives us basic math (matrix and vector operations mainly), and SciPy, which gives us advanced math (regression, optimization, distributions, advanced linear algebra, etc). There are multiple ways to install these two libraries. If you are in a hurry you can simply do

sudo apt-get install python-numpy pyhton-scipyBut that’s bad. You get old versions of NumPy and Scipy. NumPy is currently in version 1.8.0 but with apt-get you get version 1.6.1. Scipy is currently in version 0.13 but with apt-get you get version 0.9. You miss bug fixes and new functionalities and you risk having conflicts with other packages that may rely on newer versions of NumPy and SciPy.

So what I recommend is downloading the source code for NumPy and SciPy and using setup.py to install. In fact you can do this to install practically any Python package. Here is generic formula:

wget http://www.url_of_the_source_code/sourcecode.tar.gf

tar xvfz sourcecode.tar.gf

cd sourcecode

python setup.py build # "sudo" is usually not necessary to build the package; in fact, it can break the build

sudo python setup.py installAnd that’s it, almost any Python package can be installed this way. I would recommend creating a “src” directory first and doing everything in there, to avoid polluting your home directory.

mkdir src

cd srcNow that’s only a generic formula, here is what you need to do to install the current versions of NumPy and SciPy like that:

# NumPy first

wget https://pypi.python.org/packages/source/n/numpy/numpy-1.8.0.tar.gz

tar xvfz numpy-1.8.0.tar.gz

cd numpy-1.8.0

python setup.py build

sudo python setup.py install

cd ..

# then SciPy

wget https://pypi.python.org/packages/source/s/scipy/scipy-0.13.2.tar.gz

tar xvfz scipy-0.13.2.tar.gz

cd scipy-0.13.2

python setup.py build

sudo python setup.py install

cd ..And voilà, you have NumPy and SciPy.

Now, here is the thing: if you want to use Intel’s MKL then the procedure above won’t work. I mean, NumPy and SciPy will be installed, but they will not be linked to MKL. If you want to use MKL then you will need to make some changes to some of the files in the numpy-1.8.0 and scipy-0.13.2 directories before you do “python setup.py build”. What changes? Well, that’s the million-dollar question. The changes are intended to set what compiler to use, what optimization level, where your MKL/BLAS/LAPACK/ATLAS libraries are, etc. A lot depends on the details of your machine and system, so I can’t give you a step-by-step here. There are Intel directions and NumPy directions about how to do all that, but those directions just won’t work. As I said before, linking to MKL invariably involves much aggravation.

Ok, moving on to other packages.

Of all Python packages we are going to install only two are best installed by other methods. Let’s get them out of the way now:

# scikit-learn (Python's machine-learning package)

sudo easy_install -U scikit-learn

# pytz (handles time zones)

wget https://pypi.python.org/packages/3.3/p/pytz/pytz-2013.8-py3.3.egg

sudo easy_install pytz-2013.8-py3.3.eggFor all other packages we just follow the formula:

# numExpr (optimized array operations and support for multithreaded operations)

# these instructions don't apply if you want MKL; same as with NumPy and SciPy: must link numExpr explicitly

wget https://numexpr.googlecode.com/files/numexpr-2.2.2.tar.gz

tar xvfz numexpr-2.2.2.tar.gz

cd numexpr-2.2.2

python setup.py build

sudo python setup.py install

cd ..

# Bottleneck (optimized NumPy functions, written in Cython)

wget https://pypi.python.org/packages/source/B/Bottleneck/Bottleneck-0.7.0.tar.gz

tar xvfz Bottleneck-0.7.0.tar.gz

cd Bottleneck-0.7.0

python setup.py build

sudo python setup.py install

cd ..

# PyTables (reads h5 files)

wget http://downloads.sourceforge.net/project/pytables/pytables/3.0.0/tables-3.0.0.tar.gz

tar xvfz tables-3.0.0.tar.gz

cd tables-3.0.0

python setup.py build

sudo python setup.py install

cd ..

# dateutil (extensions to Python's datetime module)

wget https://pypi.python.org/packages/source/p/python-dateutil/python-dateutil-2.2.tar.gz

tar xvfz python-dateutil-2.2.tar.gz

cd python-dateutil-2.2

python setup.py build

sudo python setup.py install

cd ..

# pandas (data management tools and matrix operations)

wget https://pypi.python.org/packages/source/p/pandas/pandas-0.12.0.tar.gz

tar xvfz pandas-0.12.0.tar.gz

cd pandas-0.12.0

python setup.py build

sudo python setup.py install

cd ..

# patsy (creates "formulas" in an R-like way)

wget https://pypi.python.org/packages/source/p/patsy/patsy-0.2.1.tar.gz

tar xvfz patsy-0.2.1.tar.gz

cd patsy-0.2.1

python setup.py build

sudo python setup.py install

cd ..

# statsmodels (exploratory data analysis and some statistical tools)

wget https://pypi.python.org/packages/source/s/statsmodels/statsmodels-0.5.0.tar.gz

tar xvfz statsmodels-0.5.0.tar.gz

cd statsmodels-0.5.0

python setup.py build

sudo python setup.py install

cd ..These packages have dependency relations, so order matters here. For instance, pandas depends on NumPy, pytz, numExpr, dateutil, Bottleneck, and PyTables; PyTables depends on the HDF5 files we downloaded before; NumPy and SciPy depend on the BLAS/LAPACK/ATLAS packages we installed in the beginning; statsmodels depends on patsy; and so on. Stick to the order you see above.

It’s always a good idea to test each Python package after the installation. Most of the above packages have a “.test()” method. You can use it like this:

python -c "import package_name; package_name.test()"(You need to leave the installation directory - the directory where the “setup.py” file is - first or you get an error.)

The “.test()” method runs hundreds (sometimes thousands) of automated tests. Invariably a few of them will fail or at the very least there will be warnings. Pay attention to the failures and warnings and try to figure out whether they are related to methods or classes that you might need in your work. If you are unsure, design and run a few tests of your own, to see if you should expect any problems later. If you do run into issues then Stackoverflow and Google are your friends. If you are impatient, try installing a slightly older version of the package (although of course that may create problems of its own).

That’s it, you are now ready to start working. If you are using Amazon EC2 you can save everything you just did as an Amazon Machine Image (AMI). That way you don’t have to do everything again when you launch a new EC2 instance.

If you found all this too much work, you may want to look into Anaconda or Enthought Canopy. These are bundles that include everything I discussed above in a self-contained environment, so you don’t need to install anything; the tools are already there, even the non-Python packages like MKL (and yes, everything is already linked to MKL), so you can just use them out-of-the-box.

Unfortunately Anaconda and Canopy have their own problems. I used Anaconda for a bit but after an OS upgrade MKL just stopped working altogether (and I couldn’t disable it, so every time NumPy or pandas called MKL my code broke). Canopy, on the other hand, is not well-suited for the command-line interface, despite what the documentation might lead you to believe. I tried to set up a user environment on two different remote machines (one Ubuntu and one Red Hat) and all I got was error messages about missing libraries that I couldn’t find anywhere. So in the end I got fed up and decided to do things the hard way.